So I just competed in Google CTF. Unfortunately, I was only able to solve one problem within the competition, but I think this problem is a very interesting, and it is worth discussing about it!

KeyGenMe

Here is the problem description:

I bet you can't reverse this algorithm! attachment

tl;dr

I first ran ltrace to extract the strcmp line (to see what hash it is

comparing with), then solved for the decrypted hash, and sent the answer to

the server. Here is my python script for that:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28#!/usr/bin/python

from pwn import *

def getCheck(iden):

hasher = "ltrace ./exec2 ./elf2.patch.bin %s %s 2>&1 > /dev/null | grep strcmp | sed 's/.*\.\.\.\, //' | sed 's/...) = .*//'"

h = process(hasher % (iden, 'f' * 32), shell=True)

line = h.recvline()[1:][:-2]

h.close()

return line

def sendAnswer(p):

from binascii import hexlify, unhexlify

iden = p.recvline()[:-1]

print("Checking for %s" % iden)

inp = unhexlify(getCheck(iden))

data = [ord(inp[i]) ^ (i | i << 4) for i in range(len(inp))]

data = [chr(data[i] & 0xf | data[0xf - i] & 0xf0) for i in range(len(inp))]

data = ''.join(data)

p.sendline(hexlify(data))

p.recvuntil("OK")

p.recvline()

print("Success!")

p = remote('keygenme.ctfcompetition.com', 1337)

while True:

sendAnswer(p)

Eventually it will try to process something invalid (that's the flag), but I was lazy at that point and did not write code to process that.

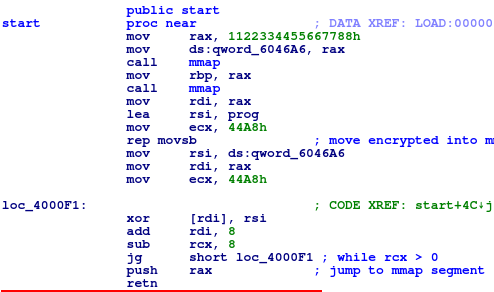

Decrypting the file

The first task that I would always do when given a mystery ELF binary is I will

pop it into IDA to check it out. When I opened this file, I saw the shortest

code... and then a bunch of data. Pretty quickly, I realized that this code was

trying to decrypt itself, and placing it in a mmap'd region. Then it invoked

itself. So I decided to extract this data, and then write a python script that

will decrypt this code for me:

The first task that I would always do when given a mystery ELF binary is I will

pop it into IDA to check it out. When I opened this file, I saw the shortest

code... and then a bunch of data. Pretty quickly, I realized that this code was

trying to decrypt itself, and placing it in a mmap'd region. Then it invoked

itself. So I decided to extract this data, and then write a python script that

will decrypt this code for me:

1 | #!/usr/bin/python3 |

I had to rewrite the python script multiple times (because I still can't seem to figure out little endian from big endian!!) Eventually, I opened up the decrypted binary file in IDA (you have to select the binary file option since this is just raw x86 code), and I was greeted with a lot of hand-crafted assembly code.

This code had a lot of syscalls embedded, so I used this handy dandy syscall

table to try to decipher all the syscall numbers. While looking through this

binary I found quite a few calls to ptrace. Initially, I thought this merely

served as an anti-debugger, (early on, the program attempted to detach any

debuggers, but I decided to patch that, so I can use strace and gdb to debug

it). Little did I know, this will come back to haunt me.

Oh some interesting construct to note. There were a few such thunk procedures, like the following:

1 | _get_data: |

When the program would call a function such as _get_data, it would first call

_thunk, which pushes the return address (or in this case, the address to the

data element), then thunk will pop this return address and then return from

_get_data. It's a little bit hairy, but it's definitely going to screw with

some disassemblers/decompilers.

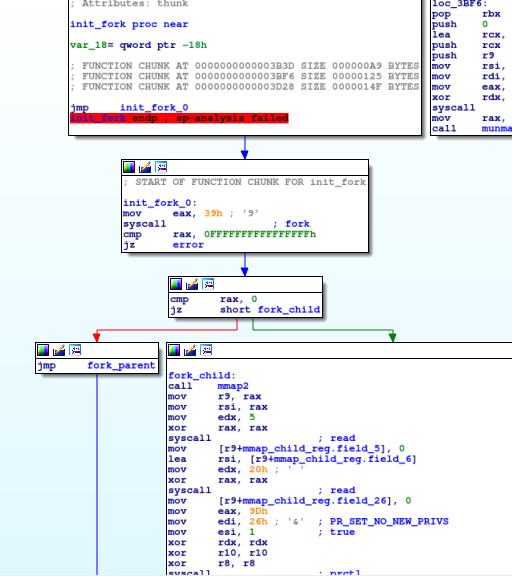

The Fork in the Road

Then shortly after, I come across this large function that executes a

Then shortly after, I come across this large function that executes a fork

syscall. I come to a part of the code where this program starts going

jump-happy. The problem is, for some reason, IDA does not know that and does not

try to mark this as part of the large function. After playing around with IDA, I

found that going to Edit -> Function -> Append Function Tail and then

selecting its parent function, you can manually add some code segment into the

function. This allows me to place this within the code flow graph of the

function. (You may have to delete any previous functions that IDA sees in this

code segment in order to append function tail).

Now there is a fork in the road, which way do I go? The parent or child? It seems like both ways, there's quite a bit of code involved. I decided to go the child first (which was the better move, I found).

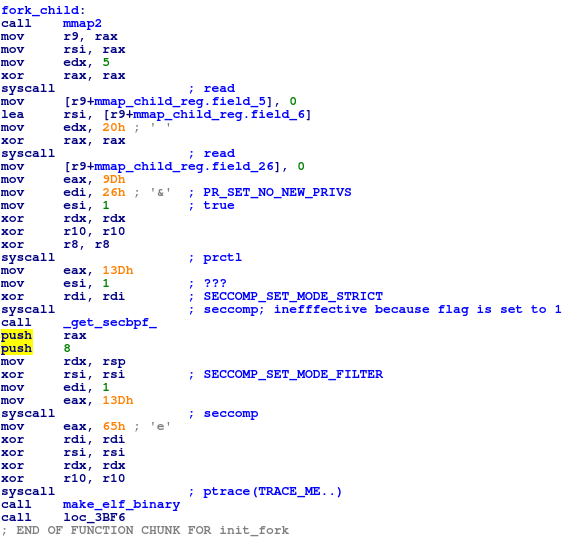

The Child's Setup

First I found two

First I found two read syscalls, of different lengths, subsequently placing

them into an mmap'd region. At first, I had no idea what it is doing, so I

decided to just skip it over. Then I found a random syscall to prctl, setting

PR_SET_NO_NEW_PRIVS to true. I had NO idea what is this code doing. I

consulted the manpage for prctl anyways, but I still had no idea why you want

to tell the kernel that you don't need anymore priviliges. Hmm...

Then the program made a syscall to seccomp. I read the manpage for it... Under

SECCOMP_SET_MODE_STRICT I found this:

The value of flags must be 0, and args must be NULL.

Hmm... I guess since the program passes the value 1 to flags, does it work

anymore...? Maybe not... Well, turns out, when I ran it with strace I found

that the syscall indeed fails:

seccomp(SECCOMP_SET_MODE_STRICT, 1, NULL) = -1 EINVAL (Invalid argument)

I guess they put that there just to fool with you. Well I guess I'm lucky to

have read the manpage with that. Then I went on and saw that the program

immediately after, made a seccomp syscall with operation set to

SECCOMP_SET_MODE_FILTER. From my basic understanding of seccomp, I know that

it allows you to filter an arbitrary number of syscalls. I allows you to create

arbitrary filters by using a bytecode called BPF (Berkeley Packet Filter),

baked directly into the kernel. It was initally used for filtering socket

packets, but then it was adapted for a seccomp syscall. I always wanted to try

this out, but never got it to work (I realized the reason why was because there

was not a glibc wrapper for the seccomp syscall, you had to make basic

syscalls to make it work).

Initially, I decided to skip over this BPF code, because trying to learn a new language is going to take a while for me. Turns out, later, I had to figure out the code anyways. Then I finally stumbled upon this part of the manpage:

In order to use the SECCOMP_SET_MODE_FILTER operation, either the caller must have the CAP_SYS_ADMIN capability, or the thread must already have the no_new_privs bit set.

Oooohhh! So that's why the syscall to prctl is made. And this manpage also

explains why this must carried out:

This requirement ensures that an unprivileged process cannot apply a malicious filter and then invoke a set-user-ID or other privileged program using execve(2), thus potentially compromising that program.

So yeah, this is a security feature, similar to why LD_PRELOAD automatically

gets removed across setuid binaries. Then the child makes a call to ptrace

with TRACE_ME. This construct is often very familiar to anti-debugging

purposes because the program can use this to check whether if another program is

already debugging it (in that case, ptrace returns an error code, and the

program can check for this code, and branch somewhere else). However, in this

code I see that the child actually does NOT check for any branch, so maybe it

uses ptrace for something else. That was when it dawned on me that maybe the

parent process is trying to "debug" or trace the child process. Then it calls a

function that extracts an ELF binary and then writes it into a temporary

memory-file using the memfd_create syscall. I decided to go into its

decryption function, only to realize there's quite a bunch of code, and I could

basically ignore most of it and just treat it as a blackbox. What I did instead,

was run gdb all the way up to the execve syscall later on, and just copy over

the ELF binary it generates (after all, it is just regular-ole file that is

actually in memory).

The parent's patching task

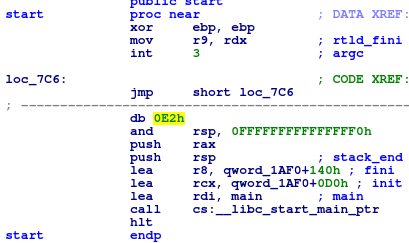

When I opened up the resulting elf binary, I was initially relieved

(Finally! I found a regular ELF binary. Glad I don't have to deal with some more

hand-crafted assembly code!) Then I noticed something was amiss. Initially, IDA

warned me that some of the .plt entries have been modified. Hmm... maybe

something is wrong? Then I found this corrupted start function:

When I opened up the resulting elf binary, I was initially relieved

(Finally! I found a regular ELF binary. Glad I don't have to deal with some more

hand-crafted assembly code!) Then I noticed something was amiss. Initially, IDA

warned me that some of the .plt entries have been modified. Hmm... maybe

something is wrong? Then I found this corrupted start function:

Ugghh! What is that

Ugghh! What is that int3 in the middle of that start function? I remembered,

that there was that TRACE_ME call that occurred earlier, so I realized it

doesn't cause a SIGTRAP signal, but it will result in the binary being stopped

until the parent intercedes. So then I realized, it is time to look at the

parent's fork process.

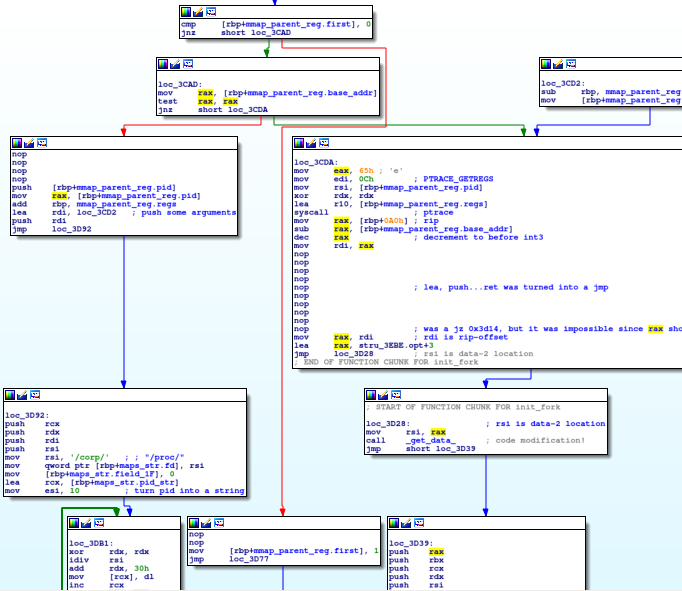

Then I started to sort of struggle a bit with this code. At this point, I was

already hours and hours into this, and I was starting grow weary of this. But I

realized I was getting close and I basically unlocked most of the code, so I

went on. I found that the parent was looping infinitely, waiting the the child

to stop (as a result of int3, which is a trap), then it first tries to get the

starting base address of the child (the binary is a PIE), and then it makes a

few debugging syscalls. Gradually I realized, it was first getting the rip

register of the child, then "patching" the code there, and restarting the child.

It also unpatches the previous stop location, so that you never get a fully

patched executable.

So I decided to come up with a brilliant idea. I ran strace with the PARENT,

filtered out the process_vm_writev syscalls (those write to another process's

memory) by passing -e trace=process_vm_writev to strace, then filtered out

those writes that "unpatched" the binary, and then patched the binary myself. I

decided to first pipe strace output to a file, and ran a few sed statements so

that I get it into the form "<PATCH>" <ADDR>. I copied the elf binary to the

filename elf2.patch.bin Then this python script will patch the binary:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15#!/usr/bin/python3

import sys

import mmap

with open("elf2.patch.bin", "rw+b") as f:

mm = mmap.mmap(f.fileno(), 0)

for line in sys.stdin:

inp = line[:-1].split(' ')

if eval(inp[0])[0] == '\xcc':

continue

data = eval(inp[0])

off = eval(inp[1]) - 0x555555554000

mm[off:off+len(data)] = data

mm.close()

Luckily, the runtime addresses ACTUALLY correspond one-to-one to the offsets in the ELF binary file. Here's the patched binary.

Breaking the code

I found that the second read that I found a while back in the child

corrrespond to argv[1] of the binary. So I gave the patched binary some value

to chew on. I ran it. Hmm... no output. This similarly happened when I ran the

actual binary. Except when I ran the network server, I get some response "BAD".

Hmm... at this point, I realized the binary they gave me, and the actual binary

running on the network server are DIFFERENT! Oh well, okay then.

I decided to run the program under strace to see what it is up to. Hmm, I'm

getting an exit_group(1) syscall. That's odd. I searched for some exit call.

Hmm... I found only one instance in some weird if-statement chain. After some

more struggling, I realized this code is decoding a hex string. What hex string?

The one I was suppose to supply as argument! Oooh! It looks like I need to

supply a hexdump of 16 characters (or 32 hexadecimal digits). So it looks like

it is failing because I wasn't giving it valid hexadecimal digits (or enough of

them). Then after giving it a proper length, I ran it, it screamed NO! at me.

Okay... you don't have to be that rude. Actually, clarification, at first it

gave me a "trap signal" because I never ran into this part of the code before.

So I reran the whole program and repatched my binary.

Then I found some sort of long-ass code that is generating a hash of some sort.

At that point I realize the zeroth argument, argv[0] was actually determined

by the first read syscall. Ohh... so I guess the network program already

supplied the first argument, and I have to figure out what correct hash to put

for the second argument. The small problem is, (well actually two), a) I did not

want to reverse engineer the code to compute the hash (it seemed so long), b)

the program actually encrypts our hash that we provide before checking.

Flags of a correct environment

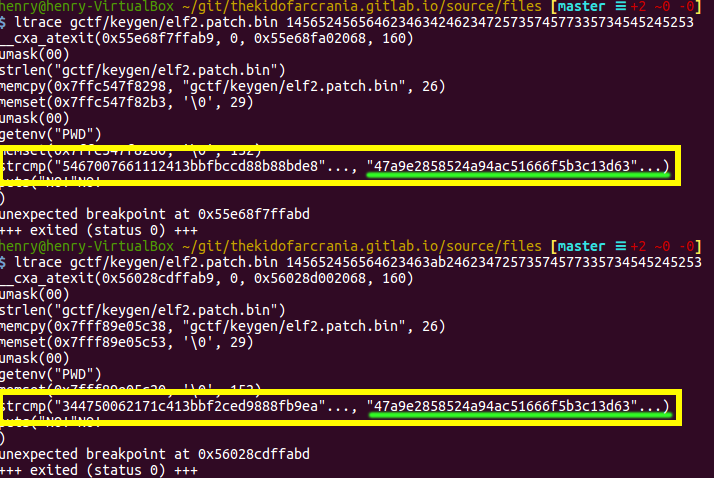

I verified this behavior by using ltrace and searching for the strcmp call:

Okay, so I guess the first hash is our input encrypted, and the second hash is

the generated one. Hmm.. but then what are those

Okay, so I guess the first hash is our input encrypted, and the second hash is

the generated one. Hmm.. but then what are those umask and getenv calls for

hmm?? I read the manpage for umask:

umask() sets the calling process's file mode creation mask (umask) to mask & 0777

Okay... so not a lot of useful information here. So I guess it sets the creation

mask to zero??? That's very weird... And I also checked getenv, it checks the

existence of the PWD environment variable, but does not actually use the

value... weird... Okay so at first I though PWD was a password environment

variable of some sort, but then I realzied that it is just the current working

directory. Then I realized, maybe the program are using these two functions as

"flags" to make sure that it is in the correct environment. Otherwise, it will

just generate invalid hashes. The getenv I caught on immediately, but then the

umask slipped out of my mind for a while. Then I realized that the BPF that I

overlooked a while back may have something to do with this. I read the manpage:

This system call always succeeds...

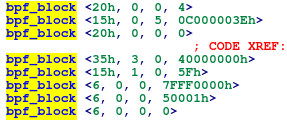

Hmm... maybe it might not succeed if there was a BPF filter for it. Here was the

BPF filtering rules:

At this point, I decided to tackle BPF again. It is actually a pretty

interesting language. It can be roughly translated into this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13 LOADABS 0x4 # load architecture type

IFEQU 0xc00000003e PASS, # value for AUDIT_ARCH_X86_64

ELSE GOTO SIGERR

LOADABS 0x0 # load syscall number

IFGEQ 0x400000000 GOTO SIGERR,

ELSE PASS

IFEQU 0x5f GOTO ERR, # check if this `umask` syscall

ELSE PASS

RET 0x7fff0000 # send OKAY

ERR:

RET 0x50001 # send error code 1 (INVAL)

SIGERR:

RET 0 # send SEGSYS

It tests to see if the syscall number is equaled to 0x5f or umask.

Coincidence? I don't think so. Maybe the ELF binary checks whether if umask is

blocked. If it is, it will generate a different hash than if it wasn't. (I did

not realize this until much, much later).

Hacking with ltrace

So I just wrote a quick C program that ran the execve syscall, passing in the

arguments to the patched elf binary.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

struct sock_filter prog[8] = {

BLK(0x20, 0, 0, 4), // LD arch

BLK(0x15, 0, 5, 0xC000003E),

BLK(0x20, 0, 0, 0), // LD nr

BLK(0x35, 3, 0, 0x40000000), //

BLK(0x15, 1, 0, 0x5F),

BLK(6, 0, 0, 0x7FFF0000), //okay

BLK(6, 0, 0, 0x50001), // errno with 1

BLK(6, 0, 0, 0)}; // kill

int main(int argc, char** argv, char** envp) {

struct sock_fprog pr = {8, prog};

prctl(PR_SET_NO_NEW_PRIVS, 1, 0, 0, 0);

syscall(SYS_seccomp, SECCOMP_SET_MODE_FILTER, 0, &pr);

umask(0);

execve(argv[1], argv + 2, 0);

}

I am proud of myself of correctly using seccomp for the first time!

To quickly figure out what this program is comparing the hash to, I just ran ltrace and extracted the strcmp call. Oh... and they encrypted the hash using an xor. I automated this whole thing with the python script mentioned before at the very top. QED.

EDIT: I forgot to also mention, they reversed ONLY the top digits of the hash

value of each byte as well, so a1b2c3d456 would become 51d2c3b4a6. I think

they did that so that the resulting encrypted code would not be too obvious.

Running the network service

There was a slight hiccup when I was trying to run the network service. Apparently, they wanted you to solve a lot keys before spitting out the flag. I have already pretty much automated the whole thing, but I was sad that it still timed out because my network lagged too much qq (probably caused by being on the other side of the world). Luckily, I had a server that could provide less network latency (that was located in the US).

I also kept on having issues with finding the correct hash to solve for because

I kept on overlooking the umask syscall block, and I kept second-guessing

myself on the getenv part. Well that's it for this problem.

Closing Remarks

This Google CTF was quite a fun event. Unfortunately, I wasn't fast enough (still) and could only solve one problem. But in the end, I thought to myself, I am still happy that I was able to solve this cool reverse engineering problem. At the time of my submission, there were only seven others, (so our team's score was really high up relative to the small number of problems that we actually solved). Unfortunately, by the time the competition ended, more than 30 teams solved it, qq. I learned quite a bit about Linux internals throughout this problem, and I think that's what matters most!

Hey! You have read all the way down here! That's cool. You want a RE challenge? I actually wrote an RE challenge a while back. See if you can find it. Start with looking at my github profile picture