So I just competed in HXP CTF with team dcua. Our team ended up fourth, which

was pretty nice stuff. There were a few fun challenges, including the

wreckme2 challenge, which I will discuss later on.

If you want to skip my rants on the easier challenges, click this link to skip directly to that one.

First I will do a write up to two other easier challenges, but it looks like LordIdiot from WreckTheLine already beat me to it. It was pretty funny cause his solutions really exactly resembled mines (or mines resemble his). I guess there really is only one solution to each of these creative problems.

Since I think LordIdiot already has a pretty good explanation about how to solve these problems, I'll explain my process of how I arrived to those same answers.

Tiny Elves (Fake)

So first had to enter a line of text, and then it will write this into a new file and execute it. The catch was (1) you can only enter 12 bytes in total, and (2) you are not allowed to enter a newline in the file (since input terminates on newline).

So immediately I turned to the #! (shebang) that is a file marker at the

beginning of regular shell files that tells the kernel to run this script with a

particular program. For example, a #!/bin/sh marker tells the kernel to run

the file with /bin/sh.

Little bit of trivia: if you look under the special proc directory

/proc/sys/fs/binfmt_miscyou can actually see all the non-ELF binary formats that are currently registered. Typically there is at least anclifile which actually interprets the#!as a "magic number". You an also use theregisterfile to add new binary formats.

So the problem is, I need to be able to get shell; I can execute any command,

but I am pretty limited in what command I can type, and also just doing

#!/bin/sh does not work because the kernel also passes the filename to the

shell interpreter as an argument, so I would not be able to drop into

interactive mode. I also can't actually type a new line to insert shell

commands.

So I searched into the manpage and found this interesting flag while digging through the manpage:

1 | -s stdin Read commands from standard input (set automatically if no file arguments |

Interestingly, this will force the shell interpreter to read from standard

input, (which is what I want). Testing on a local device, typing #!/bin/sh -s

and then cat flag.txt, it seems to print out the flag; except I can't seem to

get it work on remote. At this point, I decided to move on and dig for other

commands. I reported this to my team members, and one found that I had to issue

an exit command FIRST before the output of the flag was printed out.

Ooooohhh! I was sooo dumb here; in the python code, they are issuing a

check_output function which will read ALL the output first and then return

that, in which the python program will then write to standard output. Okay so

at that point I already had shell, but I just didn't see the output to it

because it was being consumed by check_output qqq...

Tiny Elves (Real)

This was a pretty cool problem, and fortunately, I have remembered reading an

article about this person who tried to minimize the size of an ELF binary

to the maximum. Again this time, we had to write a small binary, this time 45

bytes maximum length. Interestingly, we can pass in hex this time, BUT this has

to be a real ELF binary (since it checks the file headers for the \x7fELF

signature).

Okay so this article happens to say that the smallest they went to

minimizing the overall ELF binary was 45 bytes, not without clobbering parts of

the ELF headers to insert the program headers, and having implicit zero bytes.

If we look into the code that was given, we compute there was space for 8 bytes

of code. This pretty much means that we can't fit a shell code into here (which

can be shortened to maybe 23-ish bytes?) Anyways, even the string itself

/bin/sh is already 7 bytes, so injecting shellcode seems like a no-go.

Okay so here's the base tiny elf code from the article to reference:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29; tiny.asm

32

org 0x00010000

db 0x7F, "ELF" ; e_ident

dd 1 ; p_type

dd 0 ; p_offset

dd $$ ; p_vaddr

dw 2 ; e_type ; p_paddr

dw 3 ; e_machine

dd _start ; e_version ; p_filesz

dd _start ; e_entry ; p_memsz

dd 4 ; e_phoff ; p_flags

_start:

mov bl, 42 ; e_shoff ; p_align

xor eax, eax

inc eax ; e_flags

int 0x80

db 0

dw 0x34 ; e_ehsize

dw 0x20 ; e_phentsize

db 1 ; e_phnum

; e_shentsize

; e_shnum

; e_shstrndx

filesize equ $ - $$

I think the easiest way to go is to maybe somehow utilize a secondary system

call to bootstrap the full shellcode in a second payload. The read syscall is

probably a good candidate for this, since it has only three arguments: fd, buff,

and len, one of them (fd) which is already set (since all registers are

defaulted to zero). I just need to set the syscall number in eax register to 3,

buff or ecx to some executable address, and edx to some number. Then after

this syscall, I can just jump to this address, conviently stored in ecx. Now to

figure out what address to write to.

Initially I was wanting to do a self-modifying binary, but that meant I had to

change the p_flags to either 7 or 5 (which also overlapped with e_phoff,

which means I would have to reposition the PHT entry, which was a hassle if

don't want to unnecessarilly go through. In the end I didn't have to...

So I tried running with gdb to try to get the resulting vmmaps, scouring for some other RWX segments, not realizing that gdb is probably going to cough up on my sacriligous elf binary... well I guess that didn't work... Then I realized that the PHT entries also determine whether if the stack is RWX or not.

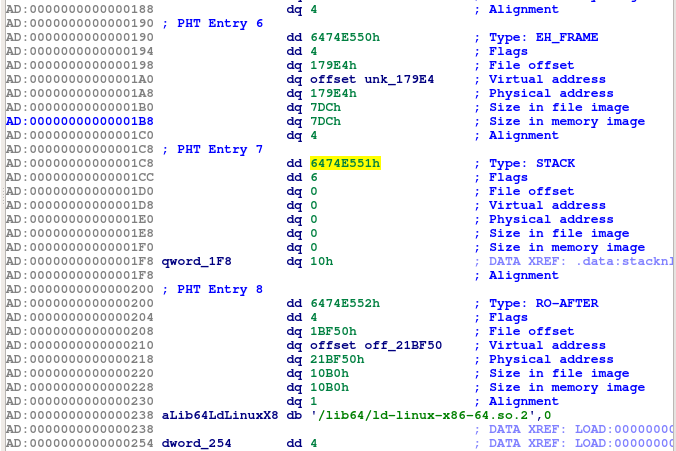

Let me explain. The PHT (Program Header Table) contains a set of entries that define memory "segments" within a program, and tells the kernel how to mmap certain program segments within the file onto the virtual memory. It has information such as the respective addresses, permissions, etc.

In a regular binary with RO stack, there is a special PHT entry that defines the stack (see below). The address field is NULL, which means the kernel will decide how to map this segment, but the interesting thing is, the permission flags will be set to 6 (Read + Write + no eXecute), thus NX. However, without that RO PHT entry, the stack is actually default to RWX, which means we can write and execute shell code on the stack.

Why is this valuable? We can set our second argument buff to a stack address

with this one line: mov ecx, esp, which is only 2 bytes! So now here's my full

tiny code that does a read-jump-exec: (I will leave full exploit code and shell

code as an exercise to the reader):

1 | mov al, 3 |

Normally, in the general case, mov op1,imm command requires at least three

bytes of code (one for the opcode, one to define the register, and one or more

bytes for the immediate value). However, interestingly, x86 actually designates

individual opcodes to do a imm to register operation for 32-bit, 8-bit, (and

16-bit if add an overload prefix) values. This effectively means that we can

code a move a 32-bit constant in 5 bytes, and move 8-bit constant in 2 bytes.

Another note: generally, the mov al, ... only sets the lower 8-bits of the

eax register, so it doesn't clear the upper more significant bits, but since

the registers are initialized to zero, that doesn't really matter.

Now if one were paying close attention, one would notice that shellcode is 10

bytes in size but we only have 8 bytes to spare. So I tried ways to optimize the

size, maybe use a one-byte inc or dec instruction, but unfortunately, it

doesn't exactly fit for increment of 3, and there is not one-byte dec

instruction variant (only one-byte 32-bit inc and dec variants). In the end,

I realize I didn't need to, since the e_ehsize of the binary can actually be

overwritten as well. So as of now, I have a full two-stage arbitrary code

execution to get shell. Yay!

wreckme2

This was an interesting binary. This problem had only 5 solves, so I was pretty happy I solved it.

So I saw this problem, and apparently this title and the description seemed to foreshadow something:

This year: - Not Haskell

- Not a crackme

To give you a prespective, I actually have NEVER touched any fully functional languages, so this was actually my first time messing around with this stuff ;)

I think I remember last year at hxp I remember opening up this program in IdaPro and realizing that this was in haskell and I was like, nope not gonna run it. (Also I had difficulties with getting the right dependencies to run it... :/ ).

Beginning binary analysis

Okay so this one is not Haskell. (Though I don't know what it meant from saying it's not a crackme. Initially I thought it meant that there might be some easy trick like with the last one, and systematic static binary-analysis would not be the best approach to solving this challenge, so I hesitated from looking much into it until later on).

I started with doing some basic static binary analysis and then did some dynamic analysis with strace and ltrace. I couldn't find much, other than the fact I noticed a bunch of function pointers that were being passed. Or at least they were passing some struct object that included a function pointer.

At this point, I thought maybe I might as well commit full on static binary analysis, since it seems like there wasn't a lot of solves, so there probably isn't really something very obvious with the binary.

Function structs?

I started digging through the binary trying to piece together how it works. So I found a data segment filled with structs containing some object with a function pointer. Hmm, I see a large number in IDA (0x100000000), I think those are actually DWORDs instead, and IDA screwed it up. Indeed when I cleaned that up, it looks like two DWORD values, the first one is a zero, and the second one is a one. Then there is a function pointer, along with some other values. Later I found that the next value is the number of arguments that function takes.

Also when I click on these functions, in IDA I see it only has one argument, regardless of how many functions it accepts. Hmm... I guess this is actually an argument vector, and this function is addressing into this vector to access arguments. So I guess that's how they account for variable number of arguments.

Oh, and I also found that each struct is 0x20 or 32 bytes long, and there are some unused fields within this? Not sure why they have them there. Maybe alignment?

A 10-argument unknown function?

Now going back, I noticed that these function structs are being passed, typically as the first parameter of some unknown function. There was an weird thing with this function, I noticed some calls have different numbers of arguments. Typically with IDA Pro, I found that they sometimes screw up the total number of arguments passed, since it doesn't actually analyze the unknown callee function, so to fix it, I clicked on decompiling this function.

To my surprise I found that this takes in 10 or so arguments, and one of them is

REALLY weird. It seems to be getting a pointer to that argument (which resides

on stack) and then incrementing from there. Hmm... after a bit more

investigation, I found that this is just actually a function with a variable

number of arguments, i.e. what happens if you use va_* and friends and say

that this function can take in some variable number of arguments. Turns out, the

code is just saving the register arguments (rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, ...) and

then referring back to them as needed.

After a bit of work, I found that this is actually gathering all the arguments to this function struct, and then calling another function, which then prepares it into some sort of function expression container.

So now I have a lot of calls to this expression creating factory, which chains a lot of calls together passing expressions as arguments to later calls (which SCREAMS FUNCTIONAL LANGUAGE), now I have a blantly obvious question: where is the evaluator?

For a moment I was searching for the eval function but couldn't find it, so I decided to continue digging through the binary. After cleaning up the code in IDA, here's the creating a new function expression function (wow that's a mouthful to say):

1 | expr *new_call(funct *func, unsigned int arg_size, ...) |

Objects, functions, references, and more...

So looking into the code we see that there's this object struct. So later I

found that there are four types of objects: functions, values, references, and

expressions. Within the "value" object there are subdivisions: chars, unsigned

longs, longs, unsigned chars, booleans, arrays (well probably I should've

labeled them structs in hindsight), and pointers.

I listed out enumerations to keep track of those types:

1 | enum ObjType { |

Another interesting thing to note, in addition to function definitions in the data segment, the program also defines some global constants (i.e. TRUE, FALSE, 0L, 1L, etc), 10/10 could've made it trolly if they modified these values during runtime, like how you can do so in old languages like Fortran.

So on I went to discovering the runtime of the functional language embedded within the program, gradually finding what each value type is and what not. Also I found that the object type value was the first DWORD mentioned earlier with the function structs, and the second DWORD was a reference counter, (the one in this field makes sense, since they are already referencable as a global object.)

The funct struct seems to be holding information about a function, and the expr seems to be holding information for calling a particular function, including a list of arguments (an array of object struct pointers) and a pointer to the respective funct struct (or is it always the case?)

Another interesting intricacy that I found was that the function pointer within a expr struct can also be a pointer to another expr object that acts like a function object. Uh-huh.. so I guess that reveals the true nature and use cases of functional languages.

It's a FREAKING FUNCTION LANGUAGE INTERPRETER!

At this point, I think I might've screamed, "IT'S A FREAKING FUNCTION LANGUAGE INTERPRETER" if my teammates were physically with me. It was a very astonishing discovery, but it doesn't stop there. I still have a functional program to parse, (which has been compiled down to C, damnit).

So after sifting through the main function I continue systematically decompiling all the function calls it make, still no eval function in sight. Then I found that on the second to last function call, it makes a eval statement, which will evaluate this long function chain. Now I have the runtime decompiled, time to decompile the functions and work my way up.

I start systematically decompiling the small base functions (add, subtract, etc.) and work my way up to the larger functions. An interesting thing was how iterating/reducing was implemented WITHOUT the use of loops (since functional languages are powerful like that).

So first an iterator would be created from a 2 element array (probably should call it a struct), and it has a type of 1. The first element is the current element, and the second element, if evaluated, will return another array of type 1 if there are more elements, or a NULL array of type 0 if this is the end. This concept is actually pretty brilliant, (and it was a PAIN trying to reverse that mess and clean up some junk especially since IDA doesn't seem to understand that type of magictry initially.) The iterator would just simply recurse itself, and return a lazy expression, which is only evaluated when accessed, hence a lazy iterator.

To reduce these elements to some result, a reducing function would then recursive call itself (via lazy expressions, of course), returning an expression that calls itself.

Reversing the Functional Program

Okay so now enough talk about the iterpreter, I want to figure out what the program is actually doing. So I kinda wanted to rush to this step, so as a result I don't think I have yet a complete grasp of the evaluation of these function expression chains. I know that you can treat an expression with incomplete arguments as a function with those incomplete arguments as arguments, but I wasn't entirely sure what the program to do if it was supplied too much arguments. But I think I found that this knowledge was sufficient enough to solve the challenge.

So essentially the program first created this iterator of fibonacci numbers modulus 0x9d. Then the program constructed an iterator with the input values (in reverse order). It then did something with the fibonacci numbers and the input value iterator, I decided to skip that for the moment, since it was HEAVILY chained, and I didn't really follow it completely. Then after something, it took the resulting iterator, checked it with an hardcoded array of values, and then printed out a smilely face or frown face depending on whether if these two values matched or not.

So now back to where the program was something with the fibonacci numbers and input values. It had something to do with some not equal comparison, an iterator that will iterate while some condition is met, and something that calculates the size of this iterator chain. So I decided to do some guessing, the only thing I thought would make sense would be comparing the input bytes with the fibonacci chain, and testing whether if that input matches a fibonacci number, and then finding the first n-th (1 based) fibonacci number that matches that input byte.

So I just wrote a quick python script that did that same code, and hoped that it

work (and it did!):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11mod = 0x9d

code = 'B7 0C 0C E9 12 17 1D 22 0f 17 09 6a 0f 0c 0c e9 5a 16 32 22 0f 1d 0f 17 52 4a 0f 54 0f 32 0f 17 52 4a 23 ad 40 22'

code = list(map(lambda x: int(x, 16), code.split(' ')))

tab = [0, 1]

for i in range(len(tab), 0x100):

tab.append((tab[i - 1] + tab[i - 2]) % mod)

print(''.join([chr(tab[x+1]) for x in code])[::-1])

And I get the flag: hxp{IT5-4-C-IT5-a-h4SkeLL-i75-ha5ceLL}.

Closing Remarks

Now I would like to say a few closing remarks. I think, like how the flag suggest, I was quite happy with reversing perhaps haskell-based? interpreter and program. It was a fun experience, learning about functional languages.

If the hxp team actually wrote a Haskell-based interpreter in C, I would like to give big kudos to them because it was really fun and unique challenge. ( I wasn't 100% sure that there wasn't just some simple wrapper that just turned Haskell into assembly code.) Though I assume this was hand-written since the reading in user input seems pretty C-like with the loop.

Anyways, however the writers do this problem, I am glad to have taken my time to do a full-on static binary analysis of this binary regardless (even though it might've taken a bit more time than doing some smart dynamic binary analysis).

Looking back, I think I would've had much difficulty had I tried dynamic binary analysis with gdb becaue this program itself was very functional-based, and trying to debug it at the assembly level would just incur pain upon me. It probably would've been easier had I insert harnesses into the actual runtime of the program, but I didn't have the time to do so. I was glad that my final blind sprint to just write the exploit script worked out in the end! Initially I was a bit skeptical on whether if my intuitions were complete and accurate, that I might have missed something.

I would like to thank hxp for putting such a cool CTF with a lot of interesting challenges.